72 Latin America and the Caribbean (LACAR): Political Geography I – The Monroe Doctrine & the Cold War

The Monroe Doctrine

By 1823, many Latin American countries had gained their independence from Spain and Portugal, or were in the process of doing so. That year, in his State of the Union address, United States President James Monroe issued a proclamation that would later come to be known as the Monroe Doctrine. It stated that once a colony in the Americas gained its independence, the U.S. would not permit a European power to attempt to colonize it. For example, once Mexico was independent from Spain, the U.S. would help defend Mexico, not only from Spanish recolonization, but also from British or French attempts to colonize it.

If you’re an optimist, you could put a positive spin on the Monroe Doctrine – that Monroe was recognizing the shared history of all former colonies of Europe, and that he was sticking up for his brethren in the Americas. And there is some truth to that. If you’re a pessimist, you could put a negative spin on the Monroe Doctrine – that Monroe was intent on replacing European dominance over Latin America with the United States’ dominance over Latin America. There is also some truth to that.

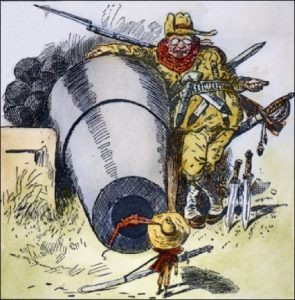

Most presidents who followed Monroe adhered strictly to his doctrine of limiting European influence in Latin America, but one president in particular dramatically expanded U.S. influence in the region. In 1898, the United States went to war with Spain, seizing Puerto Rico and Cuba, and several other small islands.

A hero of that war, Theodore Roosevelt, would be thrust to national prominence, and serve as the U.S. president from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt believed that the United States had the right to intervene in the internal affairs of Latin American countries any time the economic or political interests of the U.S. were threatened. This philosophy is often called the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.

In 1903, the United States supported Panamanian rebels in their war for independence from Colombia. Not coincidentally, one of the first actions of the newly independent Panama was to cede land to the United States that allowed for the construction of the Panama Canal. Between 1903 and 1925, the United States invaded Cuba twice, and Honduras on seven different occasions. The U.S. essentially occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933, Haiti from 1915 to 1934, and the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924. In all cases, the United States was protecting authoritarian regimes who were friendly to American business interests – that is, regimes that kept wages and taxes low on plantations and mines that supplied American companies.

This era of U.S. interventions would end in 1934 when Theodore Roosevelt’s distant cousin, President Franklin Roosevelt, instituted the Good Neighbor Policy, which pledged American respect for the sovereignty of Latin American countries. This was not, however, the end of U.S. meddling in the region.

The Cold War

By the early 1900s, there was growing frustration among Latin America’s landless and poor populations. People were frustrated with the increasing concentration of wealth and political power in the hands of the ruling class. They were frustrated by the lack of democracy in the region, and by increasing U.S. influence. Many began to embrace a communist philosophy.

Unfortunately for many would-be communist revolutionaries of the early 1900s, they had little chance of overthrowing the authoritarian governments that controlled the region. These governments were usually either dictatorships or one-party “democracies.” They were supportive of, and supported by, foreign corporations and Latin America’s wealthy. These authoritarian regimes were propped up by large militaries with huge budgets, often subsidized by the United States.

Everything changed with the dawn of the Cold War. Now, communist revolutionaries in Latin America had a significant benefactor. The Soviet Union was willing to finance and arm insurgencies throughout the region. Conflicts between American-backed governments and Soviet-backed rebels flared in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru. The United States was generally on the winning side of this Cold War chess match. Only two communist revolutions were successful – in Cuba in 1959, and Nicaragua in 1979.

The United States’ success in curbing communist expansion in Latin America came at a cost. During the Cold War, the United States adhered to what is sometimes called the “Our Dictator” philosophy. The thought was that the United States should support anti-communist dictators, because if it didn’t support “our dictator,” he would be replaced by “their dictator” – a ruler loyal to the Soviet Union.

The United States did indeed support a rogue’s gallery of dictators in Latin America. Some particularly notorious examples include Augusto Pinochet of Chile, Manuel Noriega of Panama, and the Somoza regime of Nicaragua. Pinochet came to power in a 1974 military coup that was orchestrated by the United States. He then ruled the country until 1990, killing thousands of political opponents, and torturing tens of thousands more. Manuel Noriega was an anti-communist intelligence officer trained by the United States. He ruled Panama with U.S. support in the 1980s, and had a very shady human rights record. His regime ended in 1989, when he was indicted by the United States on drug trafficking charges, and removed from power by a U.S. invasion. The Somoza family and their allies ruled Nicaragua for forty-three years, torturing and murdering political opponents, silencing the media, and violating human rights. But they were ardently anti-communist, so they were supported by the United States.

It is not coincidental that Pinochet, Noriega, and many more Latin American dictators were forced from power in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As the Soviet Union collapsed, it was no longer willing or able to support communist rebellions in Latin America, so the United States largely abandoned the “Our Dictator” policy. As U.S. support for these regimes crumbled, so did the regimes.

U.S.-Cuban Relations

Perhaps the strangest example of the United States’ relationship with Latin American can be found in Cuba. The United States granted Cuba nominal independence in 1902. In reality, Cuba was a satellite state of the U.S. for the next several decades, with a series of authoritarian regimes governing the island under the watchful eye of the American government. American companies had major stakes in Cuba’s two leading industries – plantation agriculture and tourism. Cuba exported sugar and tobacco to the U.S., and Havana was a major American playground – it was like today’s Miami and Las Vegas rolled into one. The U.S. wanted to keep taxes and wages in Cuba low to maximize profits. This led to a discontented working class, many of whom began to support a rebellion led by Fidel Castro in the 1950s.

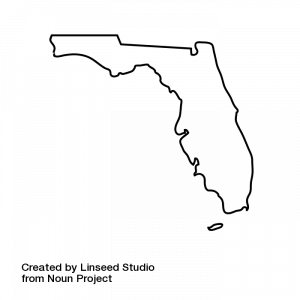

On New Year’s Day, 1959, Castro’s militia overthrew the government of Fulgencio Batista, the U.S.-backed dictator. A large number of upper-class Cubans fled the island and established residence on other Caribbean islands, or in Florida. Castro’s regime soon aligned with the Soviet Union, much to the horror of the United States. Communism had arrived at America’s doorstep – eighty miles off the coast of Florida. To the U.S., Cuba represented an unsinkable Soviet aircraft carrier.

Since then, the U.S. and Cuba have had a strained, and often bizarre, relationship. Two of the biggest flashpoints came early on. In 1961, the CIA orchestrated the Bay of Pigs Invasion (named for its landing site). The invasion was carried out by Cuban exiles hoping to retake their country from Castro. It was a spectacular failure. In 1962, the world endured the Cuban Missile Crisis. U.S. spy planes had discovered sites meant for the installation of Soviet nuclear missiles. President John F. Kennedy ordered a naval quarantine of Cuba, insisting that the Soviets remove all missile silos from the island. Tensions mounted for several days, and many feared it would escalate into a nuclear war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union eventually flinched, and agreed to remove the missile batteries in Cuba. Secretly, the United States had also agreed to remove missiles form Turkey. Reportedly, the CIA made several attempts to assassinate Castro during the 1960s (including one attempt involving an exploding cigar). None of them were successful.

Perhaps the most prominent example of the sour relationship between the two countries is the travel and trade embargo. For more than five decades, it was illegal for Americans to sell any products to Cuba, or to buy any products from Cuba. (That’s why Cuban cigars became so highly prized – they are illegal in the United States.) Americans were also forbidden, with few exceptions, to travel to Cuba. Prior to 1959, American agricultural markets and tourists had been, by far, the leading source of revenue for Cuba, so the embargo had shattering consequences for the country’s economy.

The U.S. had similar embargoes against other communist states during the Cold War, but nearly all of them were lifted in the early 1990s. The U.S. had an embargo, for example, on Vietnam. The U.S. had fought a devastating war in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, one that killed more than 58,000 U.S. military personnel. The same communist government that had fought the U.S. was still in power when the Vietnam embargo was lifted in 1993. If the U.S. had managed to bury the hatchet with Vietnam, surely it would with Cuba. But it didn’t. As the Cold War faded into the past, the United States kept its Cuban embargo in place.

This has everything to do with Florida. Florida is a classic swing state, divided evenly between Republicans and Democrats. Its two senate seats are almost always in play and, more importantly, it has 29 votes in the electoral college. In the last fifteen presidential elections, the winning candidate has lost Florida only two times. The state is nearly indispensable when it comes to a winning presidential campaign.

As mentioned above, many of the wealthy Cubans who fled Castro’s revolution settled in Florida. They and their descendants harbored bitter resentment toward the Castro regime, who had confiscated their property and forced them to flee their homeland. These Cuban-Americans are deeply influential in Florida politics, both as voters and political donors.

Nevertheless, in 2015, the U.S. and Cuba moved to normalize relations. The United States and Cuba opened their respective embassies in Havana and Washington for the first time in five decades. In 2016, Barack Obama became the first American president to visit Cuba in nearly nine decades. The two countries began negotiations to end the embargo.

The United States eased some trade and travel restrictions during President Obama’s last months in office, but the full embargo has not been lifted. There are still issues to work out. The United States insists that Cuba ease restrictions on freedom of speech and information, which Cuba is not inclined to do. There are also disagreements on economic damage claims. Cuban-Americans hold judgments from U.S. courts entitling them to $2 billion in reparations for property seized by the Castro regime back in 1959. Cuba insists that the United States pay $150 billion in damages for the hardships Cuba has suffered as a result of the embargo. Since taking office in 2017, President Trump has shown no inclination to continue negotiations with Cuba.

Did You Know?