40 N America: Historical Geography II – Housing Discrimination in the Twin Cities

This chapter was written by Nathan Dexter, applying his Geography major while living in the Twin Cities.

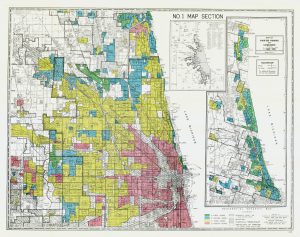

In the 1930s in President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the United States federal government created the “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation” (HOLC). What the HOLC is perhaps most famous for today is the creation of “HOLC maps,” which assigned various residential areas of cities grades for risk to mortgage lenders. Grading criteria included property values, age of properties, depreciation, and racial/ethnic makeup as well as economic class of the residents. Throughout the country, black neighborhoods were assigned D grades, meaning that they were considered hazardous for lending purposes. Though these maps were originally intended to be used for information on housing stock, they frequently also were used as guides for urban planning decisions, even for uprooting longstanding neighborhoods in favor of freeway construction.

One important example can be found in St. Paul, Minnesota. The zones D3 and D4 on the HOLC map cover two areas that were subject to extensive urban renewal and freeway building in the subsequent decades. Each zone in each city had a written description to accompany the grade. Here are some quotes from the descriptions:

D3:

“Italians, colored people, Jews of the lower strata and other people of foreign descent of the lower classes reside here.”

“Very heavy racial encroachment throughout the entire district is prominent. The only redeeming feature is its accessibility to the downtown district.”

D4 (This neighborhood was known as Rondo, a largely African-American neighborhood):

“The laboring class with a large percentage of negroes live here.”

“The class of colored people in this area are somewhat better than other districts, many of them, due to the City of St. Paul being the General Headquarters for the Northern Pacific and Great Northern Railroads, are pullman porters who do acquire ownership of their homes.”

In the following decades, Interstates 94 and 35E were routed directly through these two areas. Rondo still exists as a neighborhood to some extent, but the area covered by D3 is largely devoid of any residential neighborhoods, replaced with freeways, big box stores and light industrial zones.

These redlining practices and freeway construction projects served to enforce legalized racism in several ways. First, by labeling predominantly black districts as dangerous from a mortgage lending standpoint, black people who may have been able to afford a home were often not able to get a mortgage in their neighborhoods. Second, black residents of St. Paul were prevented from moving to other areas of the city by the use of racial covenants. Racial covenants are provisions in home deeds or titles that restrict sale of a property to non-white people. They were commonplace in the 1920s-1950s in what were considered the most desirable neighborhoods, the As and Bs on the HOLC maps. The University of Minnesota’s “Mapping Prejudice” project is working on mapping their prevalence in the Twin Cities.

Due to these factors, black Minnesotans were both prevented from acquiring mortgages in the neighborhoods they already resided in and were boxed out of neighborhoods they could have afforded and moved to. As a result, they were prevented from enjoying the boom in home equity and wealth creation that middle-class white Americans were able to take advantage of in the 1950s and 1960s. When people look back to these decades with nostalgia, much of that comes from the home equity wealth that was new to many families at that time. The financial security present in many white families today is the direct result of economic benefits that African-Americans were not permitted to enjoy.

In these areas of St. Paul, the discrimination went further. The HOLC maps were used to aid in the planning of the interstate highway system. The route that was chosen for I-94 through St. Paul was specifically intended to drive a literal rift through Rondo (D4). That this route was chosen can at best be described as disregarding the thousands of residents in the neighborhood and can at worst be considered a deliberate effort to push black people out. This didn’t have to be, however. St. Paul city planner George Herrold expressed grave concern about the social impacts of the proposed freeway route. He suggested an alternate route using the railway corridor one mile to the North (go to https://3kpnuxym9k04c8ilz2quku1czd-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/i94.jpg to see a map of these options). Herrold’s efforts were unsuccessful. It’s worth noting that everything he predicted became true. Rondo was split with huge social consequences, and the resulting creation of a concrete moat cut downtown St. Paul off from the rest of the city. Herrold’s plan would have required a negotiation with the railroads to place the freeway in that zone, and railroad companies were frequently reluctant to negotiate such terms. This meant it was politically more viable to displace thousands of residents than to negotiate with a railroad.

In these areas of St. Paul, the discrimination went further. The HOLC maps were used to aid in the planning of the interstate highway system. The route that was chosen for I-94 through St. Paul was specifically intended to drive a literal rift through Rondo (D4). That this route was chosen can at best be described as disregarding the thousands of residents in the neighborhood and can at worst be considered a deliberate effort to push black people out. This didn’t have to be, however. St. Paul city planner George Herrold expressed grave concern about the social impacts of the proposed freeway route. He suggested an alternate route using the railway corridor one mile to the North (go to https://3kpnuxym9k04c8ilz2quku1czd-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/i94.jpg to see a map of these options). Herrold’s efforts were unsuccessful. It’s worth noting that everything he predicted became true. Rondo was split with huge social consequences, and the resulting creation of a concrete moat cut downtown St. Paul off from the rest of the city. Herrold’s plan would have required a negotiation with the railroads to place the freeway in that zone, and railroad companies were frequently reluctant to negotiate such terms. This meant it was politically more viable to displace thousands of residents than to negotiate with a railroad.

Though these practices happened decades ago, they still matter today for multiple reasons. First, many people alive today saw what happened to Rondo and still remember what it was like before. I-94 wasn’t completed between the two cities until 1968. The resulting decline of Rondo led to a loss in property wealth for its residents, prompting widespread poverty. As mentioned above, African-Americans elsewhere were legally prevented from participating in the wealth generation that white Americans utilized in the middle of the 20th century. This disparity in housing wealth is a critical reason why there is such a wealth gap between white Americans and black Americans today. The government of the United States put in place a legal framework permitting the ghettoization of black people; moreover, in some cases the system extended a step further in allowing those neighborhoods to be destroyed. In its broadest sense, racial tension in America is present today because equality has never been achieved. In a specific and profound way, this inequality has been facilitated by a complex legal and social system of discriminatory housing patterns.

Did You Know?

The online edition of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune reports that for all American metro areas of at least one million people, Minneapolis has the lowest rate of African-American home ownership.

Josh Wilder’s play “The Highwaymen” examines the politics of St. Paul’s city hall in 1956, particularly regarding the planning for the I-94 highway.

For a look at the historical placement of interstate highways in six American cities, go to https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-the-footprint-of-highways-in-american-cities/

Here is a HOLC map for Chicago in 1940:

Cited and additional bibliography:

Minnesota History Center. n.d. “LibGuides: Rondo Neighborhood & I-94: Overview.” Libguides.Mnhs.Org. Minnesota Historical Society. Accessed June 2, 2020. http://libguides.mnhs.org/rondo?

Palmer, Kim. 2020. “Confronting the Black Homeownership Gap in Minnesota.” Minneapolis Star-Tribune. August 22, 2020. https://www.startribune.com/confronting-the-black-homeownership-gap-in-minnesota/572181702/.

Reicher, Matt. 2013. “The Birth of a Metro Highway (Interstate 94).” Streets.Mn. September 11, 2013. https://streets.mn/2013/09/10/the-birth-of-a-metro-highway-interstate-94/?

Silkworm. 2019. “Segregated By Design.” Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/328684375.

University of Minnesota Libraries. n.d. “Mapping Prejudice.” Www.Mappingprejudice.Org. University of Minnesota. Accessed June 2, 2020. https://www.mappingprejudice.org/?

University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab. 2019. “Mapping Inequality.” Dsl.Richmond.Edu. University of Richmond. 2019. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/?