46 North America: Urban Geography III – Chicago Common Brick

This chapter was written by an expert on this particular topic – Will Quam.

History

What can you learn about Chicago by looking at its brick? Quite a lot, surprisingly.

The first thing you may notice is that there are a lot of brick buildings in Chicago, from small bungalows to squat warehouses to towering skyscrapers. Why so much brick?

In the 1860s, Chicago was mostly built out of wood. Combined with a hot, dry summer, this made for the famous and disastrous Great Chicago Fire in 1871. Thousands of wooden homes and businesses burned to the ground in a matter of hours. After 1874, except for those far away from the city center, all buildings needed to be fireproof; naturally, that meant constructing these buildings with stone, cast iron, or brick. Of these, brick was the cheapest and most readily available material, so most buildings were built with brick.

After the fire, Chicago’s small brickmaking evolved into a juggernaut, pumping thousands, then millions, then a billion bricks a year. These bricks are known as Chicago Common Bricks, and they satisfied the need for cheaper fireproof materials. They’re slightly messy-looking pinkish-yellowish bricks that can be found on the sides and backs of buildings.

Chicago also imported a lot of brick from outside the state, including places like Milwaukee, St. Louis, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. The bricks made in these places were generally quite nice looking with crisp edges and a consistent look from brick to brick. For that reason, they were preferred for the street-facing facade of a building. These nice bricks are known as Face Bricks.

Style

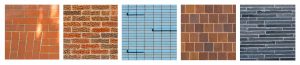

What can we learn by looking at face bricks? For one thing, the face brick of a building reveals when that building was built. Just like fashion in clothing changes from decade to decade, so has fashion in bricks and brickwork evolved! For example, in the late 1800s, most buildings were constructed using smooth, uniform red brick. In the early 1900s, red brick was replaced by speckled and lightly textured bricks. By the 1920s, architects favored multicolored brick with styled textures like waffle, bark, and rug while displaying them in wild patterns.

After World War II, architects used smoother brick and did so much more conservatively, placing brick as infill panels alongside glass and steel. The 1960s favored colorfully glazed bricks, often time stacked vertically. Since the 1970s, architects and developers have largely preferred larger, darker, and more uniform mass-produced bricks. Today, longer and thinner bricks are coming into style, as are tile-like bricks that can be laid in concrete and hoisted into place as one big panel.

Manufacturing

But why is there only one small strip of face brick on a building? Why is the vast majority of the brick Chicago common brick? The answer lies in the name: Chicago common brick. Common brick was brick that was made purely for structural purposes with little regard for appearance. Face brick, on the other hand, was very much made to look nice. Manufacturers made face bricks look nice by selecting fine clays, grinding the clay to remove any pebbles or stones. Brick was pressed hydraulically to make each brick very clean, consistent, and attractive. The process was expensive, and heavy face bricks had to be transported to Chicago from their place of manufacture, adding further expense.

In contrast, Chicago common brick manufacturers selected readily available clays and did very little to grind them fine. They were stacked and fired quickly and often featured discolored spots where two bricks touched in the kiln. They were not considered attractive, but they did their structural job and above all were very, very inexpensive to make. How cheap was it? Chicago common brick was anywhere from one half to one third as expensive as face brick. Chicago wasn’t just producing inexpensive brick; it was producing the very cheapest brick in the country! Just because it was cheap didn’t mean there wasn’t a lot of money to be made. In the 1910s, Chicago produced over one billion bricks a year, creating revenue of around $12 million. By the 1920s, Chicago was producing more common bricks than anywhere else in the country, even more than the common brickyards supplying the growth of New York City. At the end of the day, you see so much Chicago common brick because it was cheap and it was local. But wait, you may ask: Why did Chicago need to import expensive face bricks? If it was so cheap to make common bricks, why couldn’t manufacturers make their own face bricks too?

Geology

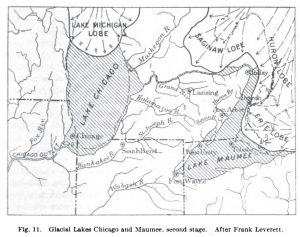

The answer lies in the ice age of approximately 13,800 years ago, when the glaciers that sat atop Chicago for a million years began to melt and recede. As the glaciers retreated, lakes formed. One such lake, an early version of Lake Michigan, was known as Lake Chicago. It sat about 60 feet higher than Lake Michigan and covered much of what is now dry land.

As the glaciers crept over the Midwest for hundreds of thousands of years, they brought with them stones and sand and clay from across the continent. As the glaciers melted, all this stuff found its way into Lake Chicago. The still waters of the lake allowed the fine particles of clay to settle on the lake bed and in the banks of the early Chicago River. As the shoreline of Lake Chicago withdrew and became Lake Michigan, those clay-rich lake beds became the land upon which the city of Chicago was built. When Chicago brick manufacturers needed clay to make bricks they barely had to search or dig. The clay was right there for the taking.

But again, why not use that clay to make face brick? Well, the clays that were deposited were quite variable. They didn’t have consistent levels of iron oxide, the ingredient that turns bricks a nice red. That’s why the Chicago common bricks burned to such a range of colors, and that wasn’t desirable for face brick.

Also, remember the other stuff that was in the glaciers? The stones? They also settled into the clay too, and stones do not make good ingredients for bricks. A large-enough stone can explode in the kiln, destroying many bricks in the process. Chicago common brick manufacturers did what they could to remove big stones from the mix, but just left many in. To pick them out or grind them down would have been incredibly expensive, especially when places like St. Louis had fine even clays that barely needed grinding.

Chicago common brick goes further back than the ice age. Those stones in the bricks are not just pebbles. They’re pieces of limestone, a stone that is made of calcified remains of the shells and skeletons of ancient organisms. These organisms were turned to stone hundreds of millions of years ago, were brought to Chicago by glaciers one million years ago, were left in the ground thousands of years ago, then were dug up and fired into bricks one hundred years ago.

Photo by Will Quam.

Conclusion

A brick in Chicago is not just a brick. It is a response to the unimaginable devastation of the Great Fire of 1871. On the front of the building, it is a stylistic choice tied to the fashions of its era. On the side and back, it is a piece of one of the most successful brick-making operations in the world. And when you look close, you can peer back in time, to the Ice Age and beyond.

Did You Know?

For more about brick in Chicago, go to Will Quam’s website – https://www.brickofchicago.com

Chicago’s Wrigley Field, home of baseball’s Chicago Cubs, features iconic outfield brick walls covered with ivy.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway, home of the Indianapolis 500 automobile race, is nicknamed “The Brickyard.” In 1909 the racetrack’s packed dirt surface was paved with 3.2 million ten-pound bricks.

The Milwaukee Bucks NBA basketball team occasionally wears uniforms emblazoned with the words “Cream City.” Probably, most people associate this term with Wisconsin’s identity as “America’s Dairyland;” however, the term actually refers to the creamy yellow color of the locally produced bricks.

Cited and additional bibliography:

Leverett, Frank, and Frank Taylor. 2014. USGS Map of Glacial Lakes Arkona and Chicago. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lake_Arkona_and_Lake_Chicago_(after_Leverett)_1913.JPG.

The Pleistocene of Indiana and Michigan, History of the Great Lakes; Chapter XVI, Glacial Lake Arkona; Frank B. Taylor; Monographs of the United States Geological Survey, Vol LIII; Frank Leverett and Frank B. Taylor; Washington, D.C,; Government Printing Office; 1915 .