99 Russian Domain: Urban Geography II – The Rank/Size Rule

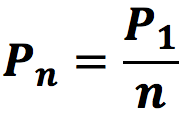

The Rank-Size Rule was derived by Harvard Professor George Kingsley Zipf. When used to express the relationship between ranked urban population size within a single region or country, it has the mathematical equation shown to the left,

where P equals population of a given city, while n equals the ranked order of that city among all cities in that region or country. Thus, P1 is the population of the number one or largest city. When applied to countries across the globe, few countries show a distribution that matches the Rank-Size Rule.

It can be asserted that countries that fulfill three specific characteristics are likely to have a population distribution that can be modeled at least to some extent by the Rank-Size Rule. Keep in mind that such a country will have numerous large cities with a progressively declining population distribution by ranked order.

First, countries that have large areas may have a rank-size distribution, for a large area allows many cities to grow significantly in size. Ever since the progressive annexation of Siberian territory, Russia has been the largest land of the world. Even before the Russian Revolution, the Russian Empire held vast lands across Siberia and over Central Asia, so that the new Soviet Union also was a huge country. The breakup of the USSR created fifteen new countries, with Russia still by far the largest. As the largest country in the world by land area, clearly Russia meets this first criterion.

Second, countries that have large populations may have a rank-size distribution, for a large population provides enough people to inhabit many cities of significant size. In 1900 Russia held a population of about 125 million people, certainly large enough to meet this criterion. However, while Moscow had gained urban preeminence from early Russian history, under Tsar Peter the Great a new city St. Petersburg was built and designated as the new capital city. With this change, St. Petersburg challenged Moscow for importance and population size. Until Moscow regained its role as capital city under Bolshevik rule in the Soviet Union, St. Petersburg’s rivalry prevented Russia from matching the rank-size distribution. The two major cities were too close together in population; for under the rank-size rule, the population of the second largest city is projected to be only half that of the largest city.

Third, countries that have a long history of urbanization and industrialization may have a rank-size distribution. In this case a sufficient amount of time is necessary for the development of a number of large cities. For this criterion tsarist rulers of Russia had brought industrialization and urbanization patterns from Europe; however, these trends were far behind those of Europe, and especially those of Western Europe. While Russia may have been ahead of countries and regions that we now often designate as in the Third World, Russia was not advanced in terms of industrialization and urbanization. This was to change, however, under Soviet rule. The dominance of heavy industry and the planned socialist economy in the Soviet Union prompted substantial industrialization and urbanization.

Thus, in the USSR all three of these criteria were met, strongly suggesting that a rank-size distribution of urban population may be present. The USSR had the large area, the large population, and sufficient years of urbanization to develop many large cities. Additionally, the secondary importance of capital cities of Soviet republics protected against the single dominance of Moscow, while the ascendancy of Moscow over St. Petersburg left Moscow as the single top city.

An examination of the 1989 population figures for the largest seven cities of the USSR indeed does show a rank-size distribution. Of course, it must be noted that the Rank-Size Rule cannot possibly predict actual urban populations down to the last man, woman, and child. Some error is expected of the magnitudes shown here. It is the general pattern and the geographic causes of that pattern that are important to understand. Indeed, using the Rank-Size Rule for 1989, St. Petersburg is projected or predicted to be 4.4 million when it actually was 4.5 million; thus, the projection was only wide by about 2%. These small variations are acceptable in demonstrating the Rank-Size Rule.

| City by Rank | Population (in millions) | Projected | Rank | % Unrounded Error |

| Moscow | 8.8 | 1 | ||

| St. Petersburg | 4.5 | 4.40 | 2 | 2.22% |

| Kiev | 2.6 | 2.93 | 3 | -11.26% |

| Tashkent | 2.1 | 2.20 | 4 | -4.76% |

| Kharkov | 1.6 | 1.76 | 5 | -10.31% |

| Minsk | 1.6 | 1.46 | 6 | 8.33% |

| Nizhniy Novgorod | 1.4 | 1.25 | 7 | 10.20% |

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union into fifteen separate countries, no longer can Russia be considered to match the rank-size distribution. This is apparent just in a careful examination of the very data above. Four of the top seven cities of the Soviet Union are not in Russia – specifically, Kiev (Ukraine), Tashkent (Uzbekistan), Kharkov and Minsk (both in Belarus). Three, as noted, were capital cities of republics that then became countries. Thus, we are left with the interesting situation that Soviet urbanization and industrialization provided the third link in the creation of the country’s rank-size distribution, but the end of the same Soviet authority has now left Russia without an ideal rank-size pattern, even though it still possesses the three expected criteria.

Statistics from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service display the continued lack of a match of the Rank-Size Rule for contemporary Russia. Here are the numbers for 2017, as they show very substantial prediction errors. The pattern of overestimating the size of lesser cities in Russia demonstrates that Moscow might be considered a primate city.

| City by Rank | Population | Projected | Rank | % Unrounded Error |

| Moscow | 12.38 m | 1 | ||

| St. Petersburg | 5.28 m | 6.19 m | 2 | -17.23% |

| Novosibirsk | 1.60 m | 4.13 m | 3 | -158.1% |

| Yekaterinburg | 1.45 m | 3.10 m | 4 | -106.9% |

| Nizhny Novgorod | 1.26 m | 2.48 m | 5 | -96.82% |

Indeed, Moscow has dominated Russia politically, since the capital moved there from then Petrograd (aka St. Petersburg) in 1918. Moscow is the focal point of Western Russia’s road and railroad networks. At its western location, St. Petersburg offers a more European vibe and a generally more striking architecture.

Did You Know?

George Kingsley Zipf was a linguist and philologist, not a geographer. The principles of Zipf’s equation can be applied to a variety of topics.

Also, the primate city distribution, where one city dominates all urban functions within a country, in a sense is the opposite of the rank-size distribution, for it is the absence of one or more of the three cited criteria that typically lead to the primate city distribution, where one city tends to prevail in all urban ways.

Check Your Understanding

Cited and additional bibliography:

“Cities and Urban Geography – Russia.” n.d. Sites.Google.Com. https://sites.google.com/a/richland2.org/russia—norman—foti-5/cities-and-urban-geography.

Iyer, Seema D. 2003. “Increasing Unevenness in the Distribution of City Sizes in Post-Soviet Russia.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 44 (5): 348–67.

Kinoshita, Tsuguki, Etsushi Kato, Koki Iwao, and Yoshiki Yamagata. 2008. “Investigating the Rank-Size Relationship of Urban Areas Using Land Cover Maps.” Geophysical Research Letters 35 (17). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008gl035163.

Lapp, G. M., N. V. Petrov, and John Adams. 1992. Urban Geography in the Soviet Union and the United States. Edited by Craig ZumBrunnen. Translated by Joel Quam and Craig ZumBrunnen. Roman and Littlefield, Inc.